Criteria for Placing Buildings at Densities Over 20 Dwellings Per Hectare

Continuity of Frontage

Continuity of built frontage is desirable because it helps to enclose spaces and creates continuous pedestrian routes. Continuity of built frontage is not always easy to achieve, but the following guidelines show how common problems can be avoided or overcome:

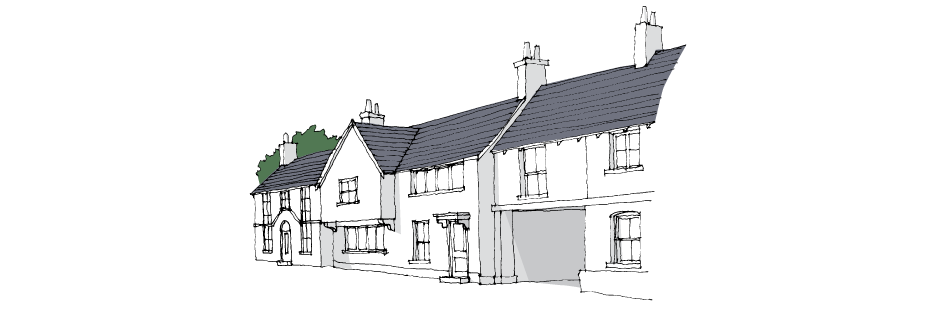

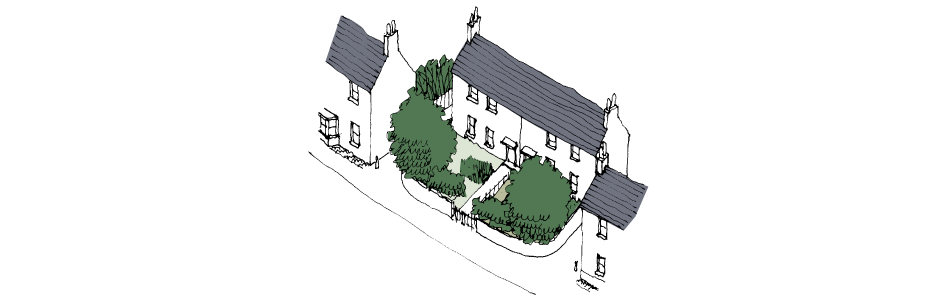

- Joining a high proportion of dwellings to each other in terraces can create a powerful continuous frontage. This need not mean suppression of the individuality of each dwelling; historic towns and villages are largely made up of individual buildings which happen to be joined to one another. Terraces are comparatively economical to construct and offer improved insulation. They are therefore energy-efficient and easy to connect to district heating systems, renewable energy sources, waste distribution systems and other digital infrastructure. If a high proportion of detached houses is desired, they should be provided within a lower density context.

- Even where space is required between buildings for vehicle access, it is possible to maintain continuity by bridging over at first-floor level.

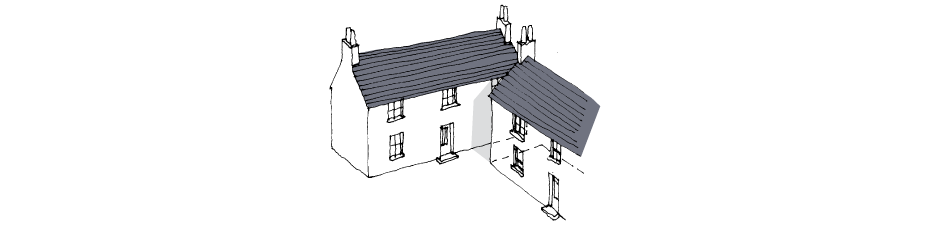

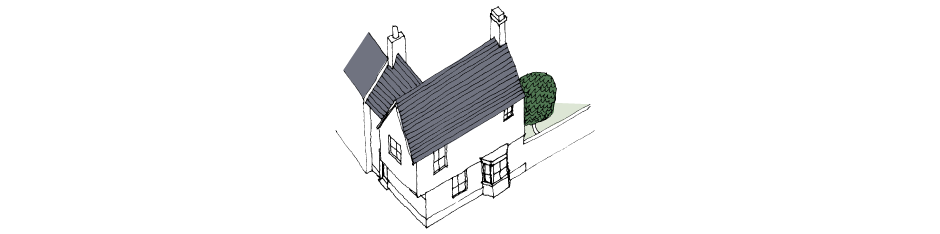

- At the ends of terraces or in the case of detached buildings, the illusion of continuity may be created by forming an overlapping right-angled corner which, when approached, conceals the gap.

- The flank of the garden of an end house is often the cause of a break in frontage continuity. Windows in these side elevations remove the bland appearance of featureless walls and allow greater natural surveillance, reducing opportunities for crime and anti-social behaviour. End houses should be designed as corner-turning buildings screening at least part of the garden flank, with the remainder screened by a wall at least 1.8m high. The length of garden walls on the street frontage should, however, be kept to a minimum.

- It is a difficult task to enclose urban space with predominantly detached and semi-detached dwellings, as the gaps between dwellings tend to dominate and the structure of the enclosed space is weakened. The use of a large proportion of detached or semi-detached houses is not conductive to the satisfactory enclosure of urban space and should be avoided in the urban context. The correct context for detached and semi-detached houses is at densities of less than 20 dwellings per hectare (8 dwellings per acre).

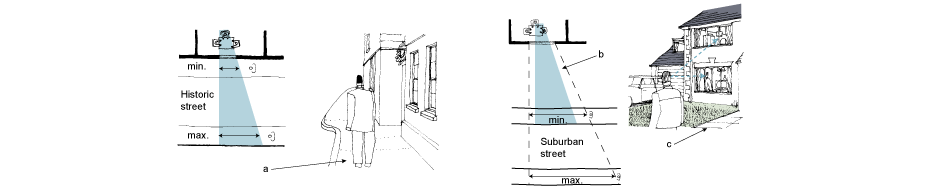

Relationship of House to Road

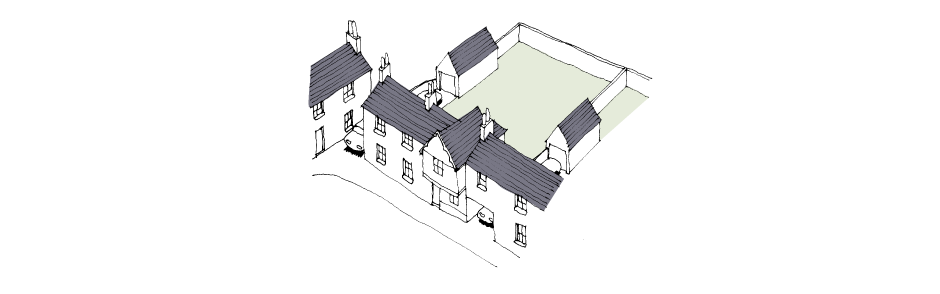

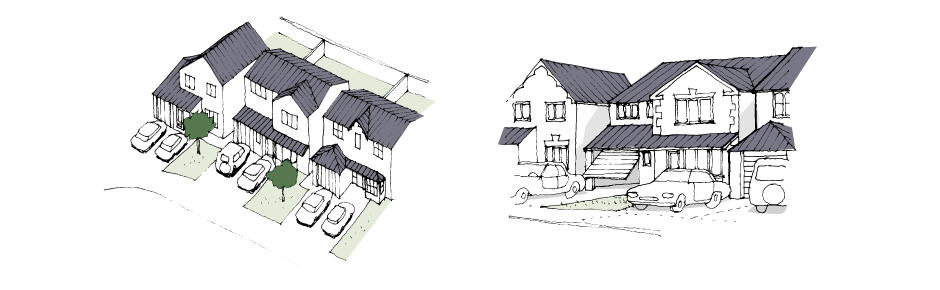

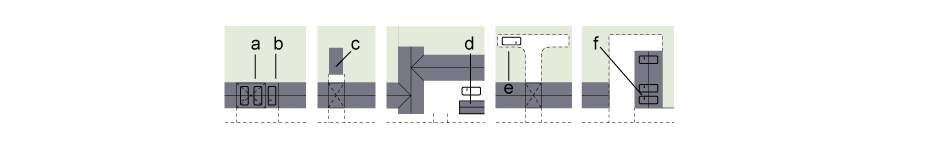

Car Parking for buildings should be sited between houses, beneath upper-storey structures or within garages to the rear, helping to reduce the visual impact of parked cars. This also has the advantage of increasing the area of the site available for private rear gardens.

Private Parking and Garages

The satisfactory enclosure of urban space becomes impossible when houses are set back from the road to accommodate private parking spaces – as may occur when houses feature integrated garages, or when they form a row of terraces without designated parking beneath or behind the houses.

For this reason, house types with integral garages should be used sparingly and/or additional parking spaces should be located elsewhere. In the case of terraced houses, visitor parking should be located at the end of or behind the terrace, unless the terrace fronts an enclosed or partially enclosed parking court or square. Parking facilities and garages must be accessible to people of all ages and a range of physical and mental abilities.

Car parking facilities should be designed with future adaptation in mind – notably the anticipated decline in private car ownership and the commensurate increase in the use of on-demand autonomous vehicles. The conversion of parking bays to parklets, garden extensions and other green spaces is significant, and could help to enhance both the visual appeal and environmental impact of a development in the future. As such, it is important to consider the location and design of car parking facilities and their relationship with the surrounding plot, street, built environment and open space – as well as how their construction allows (or can be adapted later to allow) for connection to services and conversion to alternate uses.

On-street parking may be subject to similar considerations: it is possible that the removal of car parking bays will greatly alter the perception of and relationship between the built form and the street, most obviously through a widening of footways. It is vital to plan for such changes – particularly in terms of service locations, drainage and so on – from the outset.

Cycle Storage

It is important to provide covered, secure cycle storage in a location at least equally convenient and accessible as related garage facilities. One of the greatest deterrents to cycle use for local trips is the inconvenient location (or complete lack) of cycle storage near the home. A centralised cycle parking facility may benefit a development, particularly when garages are not available for every home or space is at a premium. Cycle storage should be as secure as private storage and located so as to be overlooked by homes.

Front Gardens

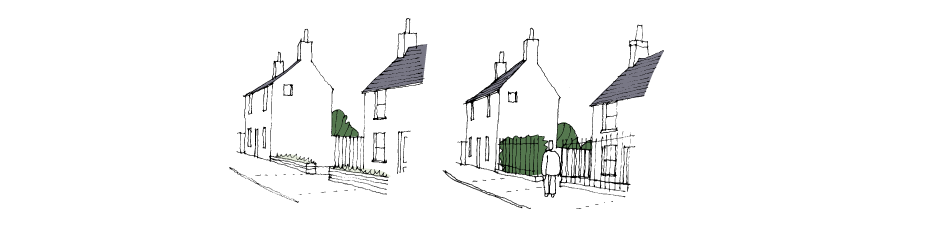

In layouts at densities of over 20 dwellings per hectare (8 dwellings per acre), there is generally no case for dwellings to incorporate front gardens, with two notable exceptions:

- One or two dwellings in a street sequence may be set back to create an incidental feeling of extra space and greenery.

- Three-storey houses are tall enough to maintain a feeling of enclosure even with front gardens – which in such cases should be large enough to contain a tree.

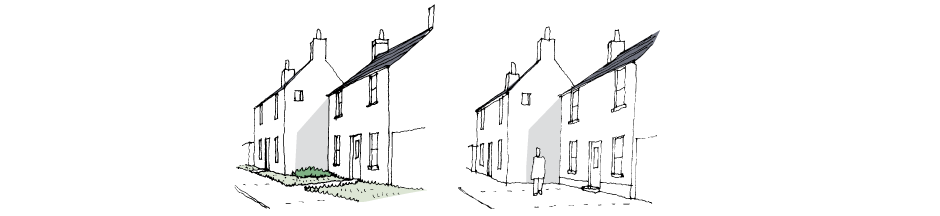

Where a layout requires that a house be set back from the road, the space in front should be either:

- a publicly accessible paved area forming part of the general street space; or

- an enclosed front garden with a wall, railing and/or hedge of at least waist height.

As ever, clear distinctions to such edges are particularly important for the partially sighted or those with dementia, who may otherwise become confused or disorientated.

All such spaces should be overlooked by windows, while alcoves and corners where intruders could hide should be avoided. Indeterminate open areas in front of houses should also be avoided. Experience shows that residents have a lower expectation of privacy from the public or access side of the dwelling; it is therefore not necessary to be as stringent in requirements for privacy on this side.

Traditionally, houses were often set forward up to the rear edge of the footway; thanks to the narrowness and well-inset nature of the windows, a wide field of vision into the interior was not offered. Where houses were set back, a hedged or walled screen to the front garden inhibited the view into the interior.

Houses that are set back with ‘open plan’ front gardens and wide windows offer less privacy from the street, particularly if they have a through living room where daylight from the rear silhouettes figures in the room. It is therefore recommended that designers return to the traditional format of vertically proportioned windows and houses either set forward to the rear edge of the footway or, exceptionally, set back behind front gardens hedged or walled to above eye-level. This accords with good practice in the creation of a townscape and the enclosure of space.

a. Visitor spaces next to garage

b. Integral garage

c. Freestanding garage at rear

d. Freestanding garage in front

e. Visitor parking behind terrace

f. Visitor parking under cart lodge at end of terrace

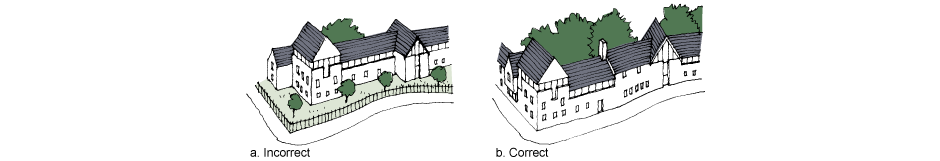

(Left) Indeterminate grassed or planted area in front visually detaches building from street to detriment of townscape

(Right) A publicly accessible paved area forming part of the general street space

(Left) Low walls, hedges or fences appear miniscule in scale and fail to offer any sense of ‘protection’ to the pedestrian

(Right) Tall railings, walls or hedges retain ‘protection’ and provide pedestrian scale

House Design Within the Context of Layout

Rather than deploying a range of house types which share the same relationship to the street, the developer should employ at least some proportion of houses which perform a particular role according to their position in the layout. The plan forms of houses should, for example, be capable of turning both external and internal corners, as this enhances both natural surveillance and passive heating and cooling properties.

A development should also incorporate houses of sufficiently distinctive design to be capable of terminating a vista or changing the direction of a road, as well as houses whose private garden side is at right-angles to their entrance side. Other useful houses are those of tapered plan form, capable of use in curved terraces or crescents, and houses of three or more storeys for use where extra height is required. There may be situations where a combination of several such attributes is needed.

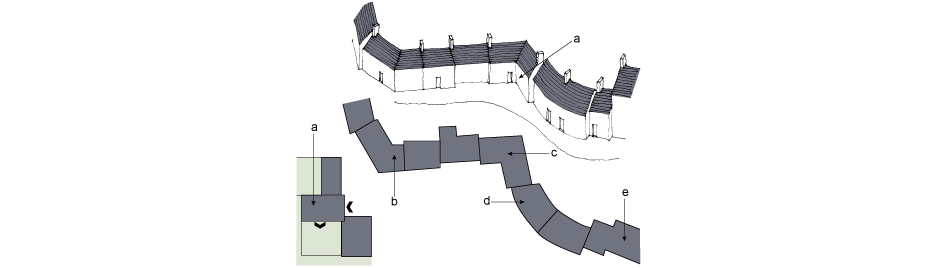

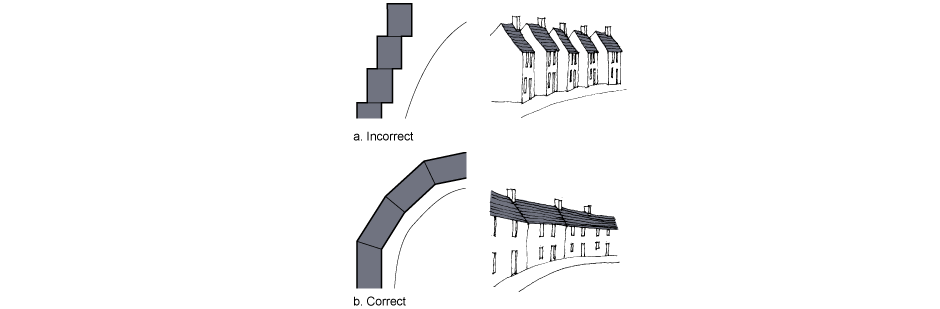

Where houses front a curve in the road, there has been a tendency to stagger the houses in a saw-tooth fashion so as not to depart from the planning grid. This is T-square planning and fails to respect the realities on the ground. It results in a jagged space and enclosing roofline uncharacteristic of traditional streets, where house fronts curve to follow the line of the street. New developments should adopt the latter method; the consequent slight irregularity of house plan is a small price to pay for a more harmonious street scene.

Flats should also form part of the street frontage instead of being set back behind grassed areas that are too public to be used.

Page updated: 9/02/2018